NEW YORK (March 8) — This is the true story behind the experimental discovery of the Higgs boson, the existence of which had been hypothesized for several decades. It has been called “the God particle,” but its prominence in what is known as the Standard Model in physics was surpassed only by its elusiveness in experiments.

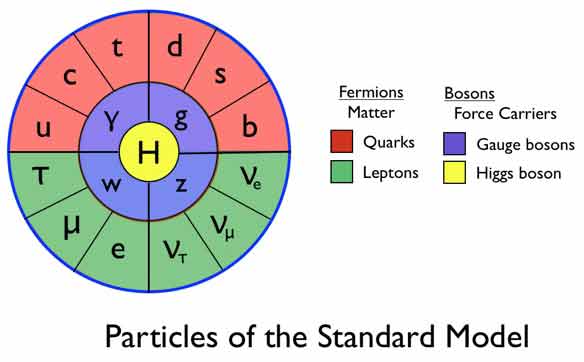

An artist’s rendition of the elementary particles

(Walter Murch, the film’s editor, via theoryandpractice.org)

Nobody had a big enough machine to see it, so this is also the story of the biggest machine ever built, 17 miles or so of microelectronics and supermagnets that need to be kept cool with liquid helium at the coldest possible temperatures.

It’s the story of people who simultaneously compete fiercely and collaborate successfully, tireless workers who write and perform rap songs about subatomic particles every time their work gets to the next phase, real-life heroes who ride their bikes to work at one of mankind’s greatest technological achievements.

It’s about people who have no idea what the economic advantages of their experiments might be in the future and are, in fact, puzzled at the question, since art and science often neither have nor need an economic motivation.

But most importantly, it’s the story of creativity and achievement at the highest level, where nothing fits into neat little packets of information but instead comes in millions of data points that thousands of people pore over for their entire lives, where they wake up one day and discover that what should have happened, according to their theories, is millions and billions of times different from what actually happened, and they think to themselves, “Gee, if I was so far off, then there must be something very wrong with what I’ve spent these last 30 years doing, and now that I know, I’m ready for retirement.”

This movie will take your breath away

It will resonate with high achievers from every discipline, scientists who suffer great setbacks after decades of work and cheerily tackle the next challenge—like the machine, known as the Large Hadron Collider, built at CERN in Geneva, Switzerland, solely to determine if physicists could catch a glimpse of the elusive Higgs boson at the center of their theories.

The machine took several years to build and cooperation from scientists whose countries were sworn enemies—countries like Iran and Israel, Pakistan and India, Russia and Georgia. All came together to build a machine capable of seeing a subatomic particle that is about 10,000 times smaller than the nucleus of an atom.

What the LHC does, on a basic understanding, is send helium nuclei spinning around in a tunnel powered by magnets. The nuclei travel around this tunnel millions of times, picking up speed until they come very close to the speed of light. One beam goes clockwise, while the other goes counterclockwise. When they have enough speed (energy), people in the control center at CERN send the beams flying into each other.

That collision is the machine’s raison d’être. It breaks the nuclei up into lots of subatomic particles, and scientists at four different experiments at CERN record the collision with something like a seven-story camera. They look for patterns relevant to their individual experiments in the massive data that emerges.

Shortly after scientists first celebrated turning the beam on, the tunnel sprang a leak, and the future of the LHC was in doubt. Scientists and technicians couldn’t exactly go out to the place where the leak occurred and put their thumb in it. The magnets had to be warmed up—slowly, so they wouldn’t break—and then removed and examined.

The damage was extensive, which gave scientists grave concerns about letting the media in the next time they fired up the collider. “If we screw this up,” with all kinds of media and camera crews in the room, CERN itself could be seen as a failure, said Fabiola Gianotti in the movie. As a spokesperson of the ATLAS experiment, she wanted to smash the beams into each other the night before the press got there, just to make sure everything was going to work.

But, everyone figured, social media would get a hold of the story and never let go, and it would be a public relations disaster.

The second time was a charm, though.

Take-home lessons (a few of them)

What is so impressive about this project, from an educational point of view, is that scientists had developed so many theories, and they all hinged on the Higgs boson. If the Higgs had a mass (energy) of 115 GeV (giga-electron volts, roughly 115 times the mass of an electron), theories that hypothesized something known as supersymmetry would be supported. If, on the other hand, the Higgs came in closer to 140 GeV, something known as a multiverse would be supported and supersymmetry would be ruled out.

Going in, nobody knew which theory was correct and which theory had been the stuff of wasted lives in pursuit of something that never was.

But to find out, they had to build the machine. What they got was something in the middle, about 125 GeV. Everybody’s theory was wrong—or at least, partially complete. This led the film’s director Mark Levinson, to reflect on camera about what he would do next.

The good news, for movie fans, is there’s always something new to discover. The LHC is undergoing upgrades now, bringing up the power, hoping to smash things into each other with more force to jar a few more particles loose and into a new class of detector. But the big subatomic particle, the Higgs boson, has been seen and recorded. The discovery was announced at CERN with Peter Higgs himself in the room when the data that proved its existence was broadcast to the world. He later shared the Nobel Prize for the theory.

It’s a story of cooperation and achievement that will inspire generations to come, perhaps more than walking on the moon did in the 1960s.